I like to go shopping at 7 a.m. Okay, that’s not true. I just so happen to be up at 6:30 to get the kids out the door by 7, and it’s convenient for me to go shopping as soon as they get on the bus. I don’t actually enjoy driving into town that early, but the store is pretty empty, the line at Starbucks is non-existent, and the drive home is peaceful.

Peaceful enough to make me think about the ancestors who are as much a part of my life as if they were still alive. Hello, I’m talking to you, great-great grandma Emma!

I’ve been blogging about Emma since, gosh 2004? Earlier? Emma has been a source of frustration ever since I was 18. I’m now 44, so that’s 26 years of said frustration.

Known records on her start in 1888, when she’s already 25 and marrying her second husband, my great-great grandfather Erastus Bartlett Shaw in Middleborough, Massachusetts. The 1900, 1910, 1920, 1930, and 1940 censuses all give conflicting information about her origin. So do her marriage certificate, her death certificate, and her one and only child’s birth, marriage, and death certificates.

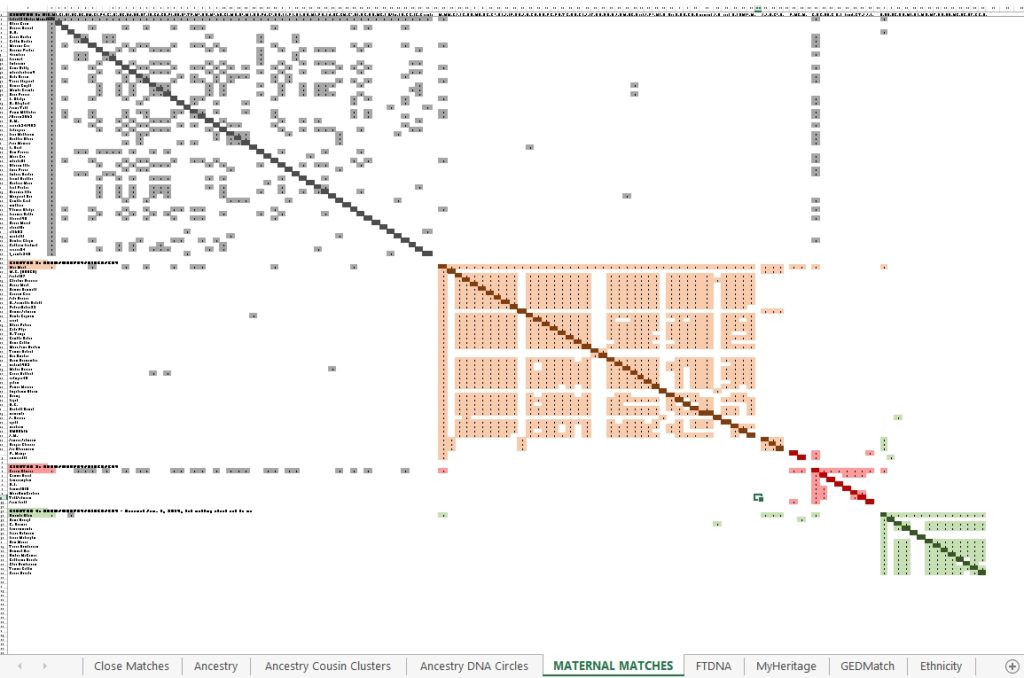

Great-grandpa Harrison Clifford Shaw, their only child, died before I was born and his wife, my great-grandma Nina (Blake) Shaw, died in January 1975, one month after I was born. So I never got to ask either of them questions. I interviewed their daughter, my grandmother, and typed my entire transcript, but she didn’t know precisely where her grandma Emma was born. My closest living link to Emma now is her great-grandchildren – my father and my aunt. Both have been kind enough to test their DNA (thanks to Uncle Pete for his help!).

And that’s been wonderful. In fact, I’ve found likely cousins on that side of the family. Not close cousins – there’s still a gap that needs to be bridged – but there is hope.

Anyway, I’m rambling as usual and here’s the thing about those quiet morning drives alongside the cornfields of rural eastern Nebraska: I have plenty of time to think.

Today I thought about money and my great-great grandma’s relationship to it. The family stories about her almost always mention money:

- She was business-minded and ran her own store;

- She showed her grandkids pictures of schooners owned by wealthy relatives;

- She buried thousands of dollars inside coffee cans in her yard, according to rumor;

- She sewed over $4000 in paper money in her dress/es, another rumor.

I started muttering to myself, as I often do when I have nothing but 15 minutes alone in my truck with a cup of coffee and NPR on in the background.

“Why do so many of the stories about Emma center around money? What was Emma’s relationship with money? What in her life informed her views on money?”

I thought about the Great Depression (1929-1939), but decided that had little relevance to Emma’s mentality about money. For contrast and additional context, I considered my great-grandmother, Mildred Marian (Burrell) (St. Onge) Haley.

I remember being 32 and how that was still a formative time in my life, learning, growing, and realizing so many things about myself. I simply can’t imagine being that age and having given birth to 7 children, all living in various homes because I couldn’t or wouldn’t care for them. Times were hard throughout the 1920s and I think Mildred never got to a place where she fully recovered or got ahead in life.

So when I consider how her life turned out and compare it to Emma’s supposed money hoarding, I think Emma’s handling of money came from a very different place than Mildred’s.

My meandering thought process led me back to my current hypothesis on Emma: that she was born an illegitimate child, that her mother was a Murphy and the daughter of the couple named as Emma’s parents on her marriage and death certificates, thus meaning her supposed parents were actually her maternal grandparents. Furthermore, it appears Emma was reared by another family. I credit Barbara Poole with discovering the only likely pre-1888 census entry for my Emma many years ago.

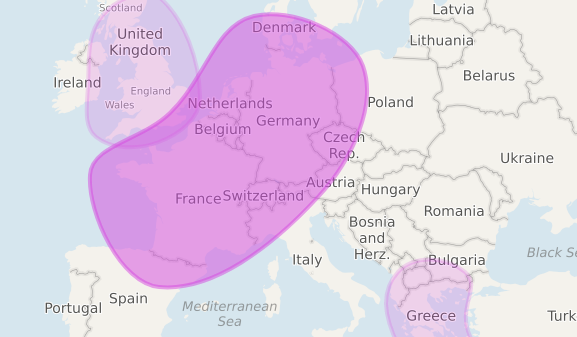

Sometime between 1871 and 1888, Emma decided to get out of Manchester, Guysborough County, Nova Scotia and find a better life. If she is the Emma I think she is, I can narrow that even further to between 1879, when she was a sponsor at a baptism in Manchester, and 1888. Her first marriage supposedly happened when she was 16, according to one census, but I have yet to find a marriage record for her and Mr. No-First-Name Regan.

Have I been able to absolutely prove my hypothesis? No. Do I think I will eventually? I hope so. It’s the one question that actually keeps me up at night. I have a consultation with Melanie McComb at NEHGS this month and hope she will give me some other avenues to pursue, because Emma remains a brick wall in my family history. I think, in the end, that it will be a combination of hitting upon the right record and my DNA network that makes it happen. But it might not be 2019, as I’d hoped…